A Planner’s Guide to History: When Wikipedia is Not Enough

Planning is a forward-looking profession – but what if you were asked to really understand the past of a place before settling on its future? Planning historian Dr. Meredith Drake Reitan offers a planner’s guide to historic research in Los Angeles.

Information about the history of a place can come from a variety of sources. This postcard from the early 1940s shows a collection of buildings that used to make up the Los Angeles civic center. Spring Street in front of the city hall building had recently been straightened, leaving the old hall of records at an odd alignment on an island of awkward shaped angles. While City Hall, the Hall of Justice and the Federal Building remain, much of what is pictured in this postcard has been demolished. The blocks immediately in front of City Hall are now the site of LA’s Grand Park.

History plays a somewhat problematic role in planning because it is the future, rather than the past, that most often guides our thinking. Planners analyze present conditions and facilitate the transformation of communities based on our understanding of future trends and possibilities. But as any planner who has tried to argue for new development to replace something older knows, communities hold tight to their history and will strenuously reject efforts to erase it.

In most university planning programs there was at least one class that looked at the history of the profession. These courses likely described planning as an increasingly specialized endeavor stemming from the ideals of Progressive-era experts. We learned about key individuals, important moments and iconic plans. Frederick Law Olmsted and Daniel Burnham probably figured prominently, as did the apocryphal fight for the Lower East Side of New York that pitted Robert Moses against Jane Jacobs. As we quickly marched through the 20th century, the influence of planning’s affiliated professions, such as architecture, landscape architecture and civil engineering, were gradually sloughed off until the profession’s core expertise in land-use management was revealed. The scale of the planning expert’s influence varied from neighborhood unit, to district, city and region, but the result of the work was typically the development of a general or master plan designed to shape an area over time.

This history of planners and of planning movements provided the foundation for our professional expertise, but did little to teach us about how to write history ourselves. Most planning documents begin with a brief history of the site or area. What if we took these context statements seriously? What if you were asked to really understand the past of a place before settling on its future? How would you begin?

Maps, like the one above, were created by the Sanborn Map Company of New York to assist fire insurance agents determine the hazards associated with particular properties. As a result, they provide detailed information about the types of buildings in an area over a long period of time. The first Sanborn maps of Los Angeles date from 1888 and were published intermittently until the 1970s. The page above shows the blocks between 6th and 8th Street at Pearl (now Figueroa) and Flower in downtown LA in 1888. At the time, the area was largely residential, made up of single family homes, a couple of schools, livery stables for horses and a baseball field. Sanborn maps are available from the Los Angeles Public Library which also provides wonderfully clear instructions on how to find an area of interest. The maps have been digitized, but their details are best appreciated in hard copy.

Good histories usually start with good source material – lots and lots of source material. The Los Angeles Conservancy has a web site with information on how to find things like building permits, tract maps and Sanborn fire insurance maps. These tools are invaluable when trying to describe the history of a building or neighborhood. For information about the social or political history of a place, old newspapers, city directories and city council minutes are also readily available.

History is not about assembling and reporting the “facts;” rather, it is about telling stories. The most important thing to remember when writing history is to acknowledge yourself and your sources as story tellers. What you write will be only one version of the past. The strength of your argument is how you use the information that you have gathered. As you compile and review sources, ask yourself the following questions:

- Have you collected enough information? A good history will go beyond easily accessible sources. For example, there is usually another side to the stories printed in the Los Angeles Times. For a different perspective, check out the city’s long-running African American-led newspaper, The Los Angeles Sentinel. The Herald and the Long Beach Press-Telegram also provide interesting alternatives to views expressed in The Times, as do the community-based journals archived in the California Digital Newspaper collection.

- Who are your sources? Think about where the document came from.Who was the author? What is the basis for their expertise? Why did they write what they did and who was the intended audience? Does the author exhibit any biases? Can you challenge the point of view?

- Do the sources you’ve collected corroborate or contradict each other? How do they differ and why?

- Whose voice is missing? It is often remarked that history is written by the winners. What would the losing side on a particular issue have to say?

- What does the visual record tell you? This also should be examined critically. Think about what the creator was trying to communicate and how they have framed the image to encourage you to see their point of view.

Once you’ve collected as much information as you can find, you will want to prepare an outline identifying key figures and dates. As you are doing this, make sure to keep track of who made what claim or who said what. Properly citing sources is critical to maintaining the credibility of your work. With a completed outline you are ready to begin writing the story.

It is important to get this right. We owe the individuals and communities we work with a thorough and thoughtful effort. By writing better histories we may come to understand the complex play of actors who contribute to urban development. Politicians, engineers, architects, landscape architects, real estate developers, civic groups, individuals and planners all played a part in shaping how we live today.

As historians Greg Hise and Bill Deverell have pointed out, looking at history offers us the opportunity to not only learn about particular events and places, but also to learn from them. A good historical analysis emphasizes the variability of the decision making process and serves as a reminder that there is nothing inevitable about the look or feel of a contemporary community or place.

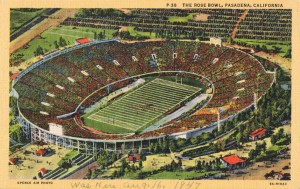

History is not about assembling the “facts” or providing a list of dates. It is about stories and individual story tellers. A hand written note on this postcard lets us know that someone “was here Aug 16, 1947.” On the back of the postcard, the original owner wrote about what a great trip they had in Southern California.

Resources

Los Angeles Conservancy Historical Research Guide

Newspapers

Los Angeles Times archive is available at the Los Angeles Public Library. On-line access is available with a library card.

LA Sentinel archive is also available at the Los Angeles Public Library.

California Digital Newspaper Collection has digitized more than 50 newspapers, including the Los Angeles Herald, the Los Angeles Star and a number of other smaller local periodicals from around Los Angeles County.

Occidental College Special Collections and College Archives provide access to many more Northeast Los Angeles community newspapers on microfilm.

Visual Materials

Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection is a wonderful source of more than 60,000 images.

USC Digital Library includes photographs, maps, dissertations and other items. There are a number of collections that are of special interest to planners including photographs from the Automobile Club of Southern California, California Historical Society, Los Angeles Examiner Collection and Dick Whittington Photography Collection. The collection of land use maps and census card surveys collected by the WPA in the 1930s is also extremely useful.

UCLA Library Digital Collection has scanned a number of photographs from the Los Angeles Daily News and the Los Angeles Times. They have also digitized about 200 photographs from pioneer LA photographer, Charles Pierce and there is a very interesting collection of images from the 1940s census mapping the city’s various racial and ethnic communities.

Huntington Digital Library has recently digitized 70,000 images from the archive of the Southern California Edison Company. The online map collection includes images from the LA County Assessor and the LA County Regional Planning Commission.

California State University, Northridge Geography Map Library obviously includes maps, but it also has an outstanding collection of aerial photographs with an emphasis on the San Fernando Valley.

Archives

The City of Los Angeles Archives and Records Center is home to LA’s “historically valuable records.” Most of the holdings have been inventoried and the contents of boxes can be viewed online. The files themselves are available to the public by appointment.

Online Archive of California provides access to the collections of more than 200 institutions statewide. A search here will tell you if more information is available and where it is located.

LA as Subject is a research alliance dedicated to preserving and improving access to the archival material of Los Angeles history. The site has an online directory of more than 230 collections many of them small and unique.

Journals

Southern California Quarterly is published by the Historical Society of Southern California. The Quarterly began in the 1930s and is a treasure trove of information about the area. Access is available to members and through many university libraries.

Dr. Meredith Drake Reitan is a planning historian and lecturer at USC. Her work has been published in the Journal of Planning History and in Planning Los Angeles, a volume from the APA’s Planners Press edited by David Sloane. She writes a blog called the lavenuesproject, which uses Figueroa Street as a frame to talk about the history of Los Angeles as a planned environment. Dr. Drake Reitan is also currently at work on a book about the LA Civic Center.