A Report from the ASLA 2017 Annual Meeting

By CivicSpark Fellows Jonathan Dolan & Jose Torres

The American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) held their Annual Meeting and Expo October 20-23, 2017 at the Los Angeles Convention Center. Two CivicSpark Water Action Fellows, representing the City of Culver City, were in attendance thanks to the support of APA Los Angeles and SWA Group. Our purpose was two-fold: to research best management practices related to our service year working on the Ballona Creek Revitalization Project and to report our experience on the APA Los Angeles blog.

This was a large conference with more than 150 events over four days, which included a combination of general sessions, workshops, field excursions, and education sessions. We selected sessions on designing urban infrastructure for aquatic habitats, the Los Angeles River roundtable, resilient design, and using the arts for infusing meaning into marginalized spaces.

The conference proved to be a refreshing and inspirational experience. It was made clear how much the arena of urban planning has in common with the ideas and approaches used by landscape architects. Both fields are driven to improve planning and design of the built environment. Besides the emphasis on aesthetic designs and renderings, there was a concept discussed of viewing the landscape architect as a “healthcare professional,” with the ability to observe the landscape holistically by reading its vital signs, delivering a diagnosis, and prescribing the most appropriate treatment.

Every panel we attended was packed with useful and inspiring information.

Urban Infrastructure and Aquatic Habitat

A panel titled Designing Innovative Habitats: Urban Infrastructure and Aquatic Habitat featured two examples of how landscape architecture provided the necessary prescription for the ailing ecology of two bay waterfronts in Seattle, Washington and Baltimore, Maryland. In both cases, the approach “turned landscape design on its head,” by keeping the focus on habitat. The key stakeholders in these two waterfront projects were the flora and fauna: juvenile salmon in Seattle’s Puget Sound and oysters in the Baltimore’s Inner Harbor.

Seattle, Washington

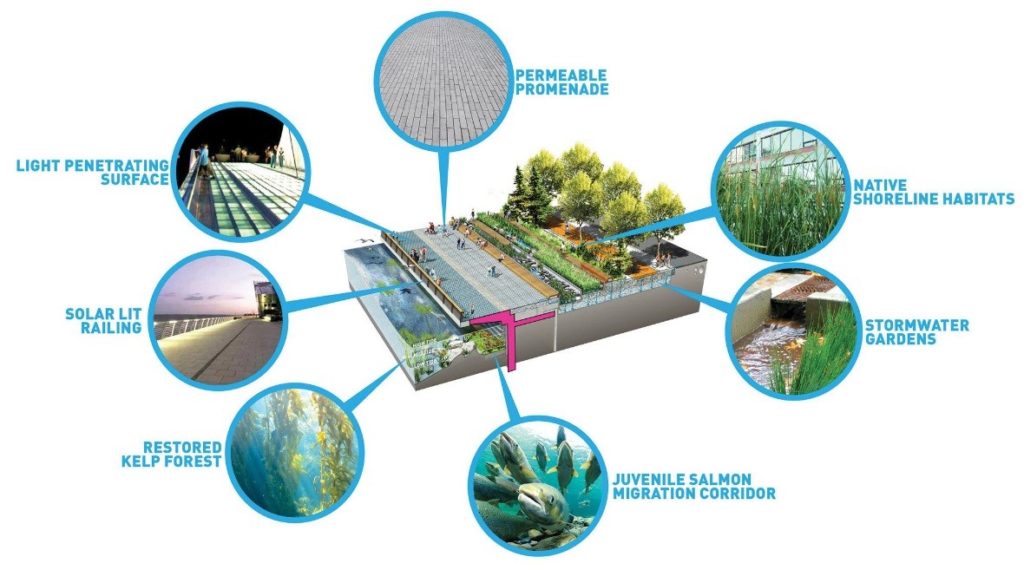

Panelist Andrew tenBrink, ASLA, a designer at JCFO, has been working on the Seattle Central Waterfront project since it started in 2010. Mr. tenBrink discussed how a habitat focused landscape architecture plan can be a transformative approach, and a voice for the voiceless. The Seattle Waterfront project had four project goals: 1) replace the seismically damaged seawall, 2) replace a viaduct with a tunnel, 3) build new roads for accessibility, and 4) expand the public realm. Ultimately, these four goals were driven by the consideration of juvenile salmon migrating along Puget Sound. The result was a beautifully thought out design which incorporated textured walls, rock mattresses, and a structure which featured a light penetrating surface. These design components, ensured higher levels of light and shallow waters important for healthy development of migrating juvenile salmon.

Seattle Waterfront Redevelopment (Source: James Corner Field Operations)

Baltimore, Maryland

Years of environmental neglect have polluted Baltimore Harbor, leading to increases in algae blooms and subsequent fish kills. Panelist Jennifer Dodwell, ASLA, described a pilot project in collaboration with the National Aquarium and Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore, Inc. (WPB). This partnership was driven by the WPB’s Healthy Harbor Initiatives, with the goal of ensuring a “swimmable and fishable harbor by 2020.” One of the eight initiatives integrates floating wetlands for the purpose of ecological restoration. Floating wetlands are artificial structures made of plastic or foam which can hold endemic flora that over time grow roots below the water’s surface. Floating wetlands have multiple functions including biofiltration (the removal of excess nutrients from the water), providing habitat with ample and cool shade for fauna and other microorganisms, adding strikingly beautiful landscaping, and attracting migratory birds.

Floating Wetlands in Baltimore Harbor (Source: National Aquarium)

Infusing Meaning Through Art and Design

A particularly motivating session was Marginalized Spaces: Infusing Meaning Through Art and Design. The panelists included three landscape architects and a planner. A story told by Aaron Paley, urban planner by training and current President of Community Arts Resources (CARS) was especially fascinating.

In 2008, CARS initiated discussions for proposing an open streets event in Los Angeles. Their model was based on Ciclovía events that started 40 years ago in Bogotá, Colombia. Ciclovía is a Spanish term that means “cycleway;” meaning either a permanent bike path or the closing of certain streets to automobiles for cyclists and pedestrians. The first such event in Los Angeles was held in 2010, appropriately called “CicLAvia.” Since its inception in 2010, there have been 20 CicLAvia events, hosting more than a million participants cycling or walking over 140 miles of open streets.

Paley talked to the audience about a 14-year old that has been participating in CicLAvia since its inception. He explained that to that young person, making the streets open and available to people and their bicycles by closing access to cars for just one day out of the year is a completely normal thing to do.

For that young person not at all out of the ordinary. That sort of thinking is reflective of the type of cultural shift which is taking place today among the younger generation: being able to walk or bike to work; being allowed to infuse work with play; leading happy, healthy and productive lives that are not auto-dependent; being able to shut down the streets in the name of cyclists and pedestrians for the sake of public health, welfare and safety.

This shift in attitude reflects a broader trend to undo plans of the past, which often lacked the foresight of the health and environmental consequences of their actions. Today, many landscape architects and planners are at the forefront of a movement to protect and restore natural features that provide essential ecological services and much-needed recreational space. The ultimate goal is to return natural elements and natural processes to urban spaces, reconnect people with the land, and create healthier and more sustainable environments.

CicLAvia on Washington Blvd in Culver City (Source: ciclavia.org)

Urban Ecology

The ASLA conference reflected the importance of factoring historical ecology into the planning process. Integrating natural elements and processes into urban space undoubtedly provides the basis of the new school of planning thought. However, the question then arises: how can planners and landscape architects ensure that maximum benefit is derived from natural space? Creating well thought-out, comprehensive plans becomes even more important when one considers the limited extent to which naturalization can be achieved. Restoring full ecological function to modern cities isn’t feasible given population growth and present living standards, so prioritizing plans based on benefit is necessary.

Some planners and landscape architects, like Julie Newman of US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), spoke of the importance of interdisciplinary approaches to the future of planning and landscape architecture. Planners and landscape architects closely consult with people of various backgrounds, like anthropologists and local tribal representatives, to ensure maximum benefit for all people and natural resources. Cooperation also allows planners to buffer themselves against the dangers of linear thinking. This same style of thought ultimately led to the present degraded conditions of important natural features like the LA River. According to Lewis Mac Adams, head of Friends of the LA River, “Last time there was a single vision for the LA River it involved 3 million barrels of concrete.”

Though driven towards progress, planning is also inherently linked to the past, which provides lessons learned and local context for projects. Conventionally, growth has played a key role in defining planning objectives and operations. Growth in itself isn’t deleterious, but it becomes harmful when it stresses short-term gain over long-term viability and favors a particular group of stakeholders.

Accounting for multiple viewpoints while making progress is a major challenge, particularly while navigating today’s rocky socio-political landscape. However, groups like SWA honed in on a golden rule at this conference: the chaos of overlapping environments, cultures, and attitudes can, under the right circumstances, create a beautiful urban quilt. Embracing the challenges inherent in working within the context of this complex structure generates incredible opportunity to reshape the cities of the future. Decisions planners and landscape architects make may not always be popular, but the results can motivate change on a broader scale.

Jonathan Dolan grew up in North Carolina and graduated from UNC Chapel Hill in May 2017 with a bachelor’s in biology and a music minor. His deep-rooted love for all things green, and his keen interest in the interactions between people and urban and natural spaces, has inspired him to pursue a career in conservation.

http://civicspark.lgc.org/2017-18-fellows/entry/3692/

Jose Torres is passionate about arts integration, community development, and hazard mitigation. He holds a bachelor’s in Chinese Language and Literature from UCLA, a master of science in Traditional Chinese Medicine from Dong-Guk University, and most recently completed a dual masters from Auburn University in Geography and Community Planning.

http://civicspark.lgc.org/2017-18-fellows/entry/3743/