Our Neighborhood Then and Now: Redlining, Gentrification and Housing in Los Angeles

This is the third installment of a three-part series.

“The Marshalls were close to their Japanese-American neighbors, particularly the Hoshizakis and the Kakibas, who lived on either side of them. Their daughter, Barbara Marshall, remembers food and culture being exchanged over the hedges of their houses.” – Samanta Helou-Hernandez, This Side of Hoover

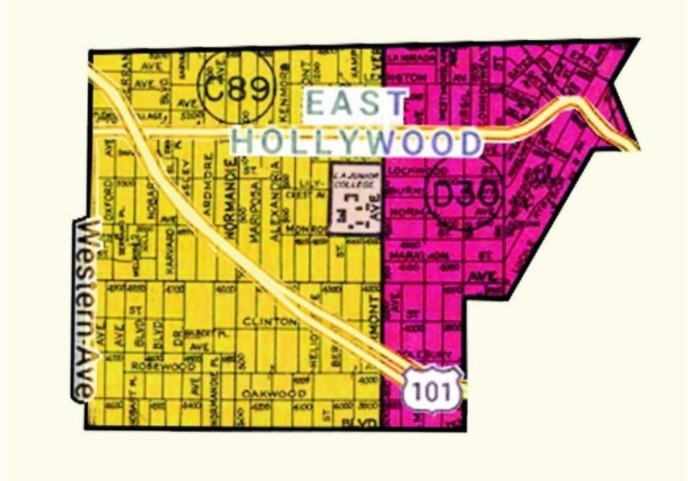

The Japanese American and African American families documented on This Side of Hoover were the types of families in East Hollywood whom a band of real estate appraisers & L.A. County officials in the 1940s would come to label “undesirable” for investment. Today, the area, east of Hollywood and west of Silver Lake, is a majority-immigrant community where nearly 4/5ths of the population rent apartments, and which is also disproportionately policed over increasingly valuable real estate for appraisers.

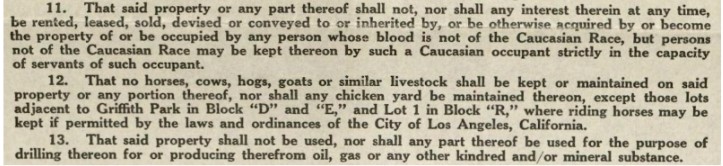

Now, nearly one hundred years since deed restrictions in Los Feliz–a wealthier neighborhood to the north of East Hollywood–stated in their clauses that only members of the “Caucasian Race” were allowed to own property in the area, Black residents there and in East Hollywood now face the highest rates of homelessness and policing of their bodies. Non-white immigrant communities face the second highest rates of homelenessness and policing in Los Feliz and East Hollywood.

Data also shows from 1980 – 2014, when areas like East Hollywood saw their largest waves of immigration from Latin America and Asia, rents in Los Angeles jumped 55%, even as incomes increased only by 13%.

In 2018, according to the California Housing Partnership (CHP), “Renters in Los Angeles County [needed] to earn $46.15/hr – more than 4 times local minimum wage – to afford the median monthly asking rent of $2,400.” The CHP also estimated that Los Angeles County needs at least 568,255 additional affordable rental homes to meet current demand. The number of needed affordable housing units is also likely increasing daily due to Ellis Act evictions.

Ellis Act evictions take place when landlords decide to convert buildings, including rent-stabilized (RSO) buildings, into condominiums. Since 2000, Ellis Act evictions have taken nearly 500 housing rent-stabilized units out of East Hollywood and nearly 27,000 RSO units from the city of Los Angeles overall. At the same time, since 2000, homelessness in the 13th district, of which East Hollywood is a part of, has only accelerated, with at least 544 families without housing as recently as 2019. The total number of unhoused people in the 13th district is now at least 4,000 since 2019, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.

As we discuss redlining in East Hollywood then, it’s also important to note that Los Angeles was not always segregated between wealthy neighborhoods on the west and north sides and impoverished neighborhoods in the central, east and south sides. Redlined neighborhoods in Los Angeles actually meant that neighborhoods were integrated, made up of Black, immigrant, and European-born residents. The clearest consequence of redlining and related policies then was explicit government investment in dividing cities by racial makeup, which eventually came to promulgate the false notion that universal human necessities like housing, education, and healthcare should serve only some residents at the expense of others.

Also consider that Black and immigrant groups called “undesirable” for investment by the Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) were groups of laborers, many of whom worked for the city’s biggest industries in the 20th century before WW2, that of service and agriculture. Black, Japanese, Mexican and other “minority” residents served wealthier white families in areas like Los Feliz as babysitters, nurses, fruit pickers, and more. Historically then, Black and immigrant communities in Los Angeles played critical roles in making the state of California the fifth largest state in the U.S. by 1950.

Redlining also entailed private and public officials marking people as inherently hazardous to one another due to racial difference, not unlike an unsafe “building condition.” For example, there were certain parts of the northern portion of Hollywood that were redlined not because Black or immigrant people resided there, but due to an unsafe dam.

Private and public officials feared–or at least professed–that racially different groups living together could only lead to racial rioting, which was prevalent from the 50s – 60s, though largely over the same issues: housing, employment, and police discrimination against Black and other non-white bodies. But if groups of different skin color could only lead to rioting, then what explains the inter-ethnic community between Black and Japanese American families like those noted by This Side of Hoover’s reporting work? Instead of rioting against one another, different groups in Los Angeles, including Black, immigrant and also white, have continually come together in East Hollywood even without much support from local, state and federal officials. They still do.

Here are also a few interesting questions for readers to consider about any redlined neighborhood in the U.S. today: What would the area look like today if Black and immigrant communities had actually been invested in, or allowed to own homes in “white” neighborhoods and supported sufficiently in doing so? How many unhoused “tent cities ”would have failed to form in the decades after the 1940s? And how much crime and policing over the last 80 years could have been avoided in the neighborhood?

Now Los Angeles is witnessing the rise of a new generation of multi-ethnic groups organizing to advance justice and equity in the city, particularly in the area of Tenants Rights. More interethnic movements need to be forged, however, at the same time that the vast majority of L.A. and California’s public officials continue to seem as distant as ever from work on the ground towards equity.

But if Los Angeles needed a reminder that Black people have worked to advance justice for ALL groups, or create justice where it was left wanting, including in this city and not just the historic U.S. south, Ms. Marshall’s account of her family visiting their Japanese American neighbors preceding their internment with sweets and other shows of friendship demonstrate it loudly and clearly.

“I didn’t know we were in an integrated neighborhood until I learned about that word. To be able to walk down the street without fear of people calling you names because everybody was part of the neighborhood.” -Barbara Marshall

Ms. Marshall’s endearing description of everyone belonging to the neighborhood is precisely why the pamphlets for Making Our Neighborhood were translated into four of the most spoken languages in East Hollywood today, including Español, Thai, Tagalog, and Armenian. Our pamphlets have been well received by the community, and for good reason: In a city where at least 3/4ths of the population can trace roots to languages other than English, our informational pamphlets hint at what the next chapter of city planning and community engagement need to look like.

In today’s Los Angeles, every resident, whether in the celebrity or political class, or not, is a part of this city. Indeed, this simple understanding is all that was missing during the days of deed restrictions, redlining, and other discriminatory practices in home-sales or home rentals to non-white communities. It’s the city that “should have been” built at the dawn of the twentieth century, but that we have to build–and fight for–now.

Consider that during the most fatal public health crisis in over a century, civic groups have taken almost no break hounding at L.A.’s political leadership to “seize the hotels” in order to temporarily shelter L.A. County’s 67,000 unhoused residents, who are predominantly Black and immigrant residents, even as the federal government ensures 100% reimbursement for this procedure. The fact is that given Los Angeles Housing policy for non-white and immigrant communities over the last 100 years, the neighborly thing for our civic and political leadership to do would be to ensure such common sense calls don’t have to be made. Yet nothing remains guaranteed. As our communities have done since the beginning, the current generation also has to fight for a more humane city and community.

At the same time that our communities fight to shelter the unsheltered, we also have to protect what affordable, rent stabilized housing remains in Los Angeles. Finally, we need to amplify calls on our political leadership to stand up to developers on behalf of our neighborhoods as they were elected to do.

Remember: The CHP has noted that L.A. County is behind, by over 568,000 affordable housing units and then some. Yet if there’s one thing L.A. was known for since before the 20th century all the way up to 1951, when talks of a baseball team coming to L.A. were just getting started, it was setting records, including building records and booms.For our part, as storytellers, our research and documentation work uplifts elders, activists currently on the ground in our communities, scholars, and even more of what makes East Hollywood and any neighborhood like it more than just “worth” honoring for a moment, but something worth honoring at length for a future.

Already, we have taken the historical truths of redlining and gentrification and flipped them to serve more than just one group or narrative. Our political officials can do the same, and then some. Find our recorded panel sessions on YouTube, and pose your questions for us at our new website for the rest of our community: Hope.xyz/MakingOurNeighborhood.